Thinking About Clusters In A Cluster

I got a little meta at the Southeastern United Grape and Wine Symposium and lived to tell the story.

On the patio of Windsor Run Cellars, winemaker Elizabeth Higley cracks the crown cap of a purple potion in a labelless, clear bottle. She sets it down on the center of the table and the four of us hunch down like synchronized swimmers to witness the fizz from below. “That’s a perfect bubble!” Taylor Greene says. Higley pours the coferment into our glasses as the sky around us fades from Carolina blue to lavender, the stars fading in.

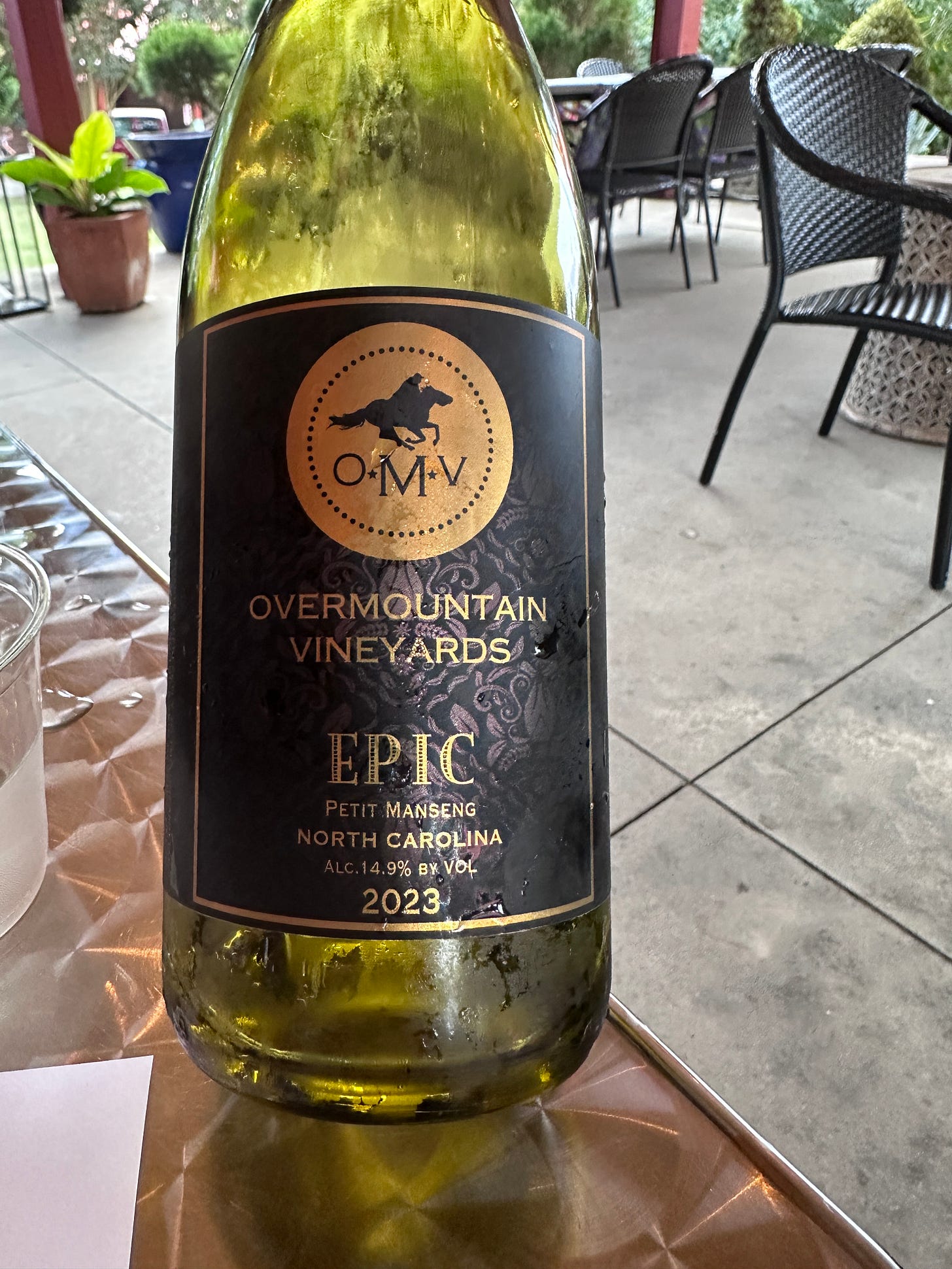

We take a sip; it’s dry, fruity, bright, and stemmy. “I’m happy with that,” Higley says and we all start talking about Lambrusco. Many moons ago the four of us sat around another table, surrounded by Cuban art and hydrated plants at Overmountain Vineyards, an hour and a half west. Higley was there to buy the blueberries she would later coferment with Chambourcin to make the wine we were drinking now. I was there with Greene, who also works in wine, and her wife who, as a result of helping Greene study for her recent CSW, knows more technical information about European wine than me. We were there to taste Petit Manseng, a few Bordeaux varietals, and Muscadine, and to meet the winemaker, Sofia Lilly, who would, in a few months, become one-third of a major relief operation in the wake of Hurricane Helene.

What a trip to skip forward in time through all that has happened while this wine patiently fermented into something cohesive, something that would aid the necessary unwinding that harvest, a hurricane, and a presidential election would bring. The day before, we all attended the Southeastern United Grape and Wine Symposium at Surry Community College, facilitated by the team at Surry, including another powerhouse of N.C. wine, Sarah Bowman, who I’d had the chance to interview before. Bowman has been the viticultural instructor at Surry Cellars for six years, a program that has created winemakers all over North Carolina, including Higley.

Old and new heads in the N.C. winemaking scene popped up in the main room with their bottles after an afternoon of hearing speakers from Virginia, California, and Washington. Eric Patterson, a South Carolina native working on a PhD at UC Davis presented on a term he’s coined that allows for an analysis of wine that widens the lens of terroir to include cultural and historical elements: “winescapes”. He spoke about clustering, where communities thrive in geographical closeness and create “vortexes of research”. That day we would wander into the Surry CC teaching winery where Enology Instructor David Bower would pop open a bright pink varietal of Muscadine that sounds more like a strain of weed than a wine: RazzMaTazz.

And the next day, we’d gather around this royal purple bottle of bubbles under a half moon as Higley pointed out the Amish buggy rolling down the road. Windsor Run Cellars is in the Yadkin Valley in Hamptonville, North Carolina’s only Amish settlement. In addition to its own label, Windsor Run offers custom crush services for several North Carolina winemakers and runs a distillery. A walk through Windsor Run’s production building might bring you to a tank of carbonic Muscadine, Valvin Muscat, Malbec, or liquor distilled from Traminette.

At the symposium I got to meet an internet friend IRL: Reggie Leonard II presented an account of exactly what he’s done to cultivate community in Virginia. From inviting non-trade people to curate wine events to redirecting national press inquiries to regional writers, he seems to be shaping a world that he is genuinely interested in living in. His events are original, enthusiastically creative, and embody inclusivity in a way many wine events and initiatives don’t. The gates have fallen off their hinges in Virginia and being able to witness that might just be what any wine community needs to become certain that they can do it too.

The following month, I would drive up the East Coast to New York, stopping in Virginia to sit at the bar of Common Wealth Crush Co. with Leonard II and get a taste of what life is like in that particular cluster. In the Hudson Valley of New York, I’d find many things that reminded me of western North Carolina—particularly the long stretches of road between each winemaker, who might be making anything from a natural Cayuga to a Champenoise.

The Hudson Valley wine scene is young, experimental, and full of energy. As I drove all over the region and then back down I-81 toward North Carolina, I began to think of the entire East Coast wine scene as one long row of vines. In the vineyard, (most) wine grapes grow in clusters, and all kinds of efforts are made throughout the year to ensure that clusters ripen evenly—within themselves and with each other. Where clusters like Surry CC, Windsor Run, and Common Wealth Crush exist, I’ve found consistency, quality, and community in bloom. So the question I have is: how can I encourage even ripening of the wine scenes throughout Appalachia?

As I scheme about this a bit, I’m going to unpack what I learned on my road trip (it gets existential) and for paying subscribers, I’m revisiting my first international press trip to Mount Etna in Sicily where I tasted Nerello Mascalese and Carricante hundreds of times in three days.