The first days after Helene and the winding road in front of us

Dispatch from the wine world of Southern Appalachia.

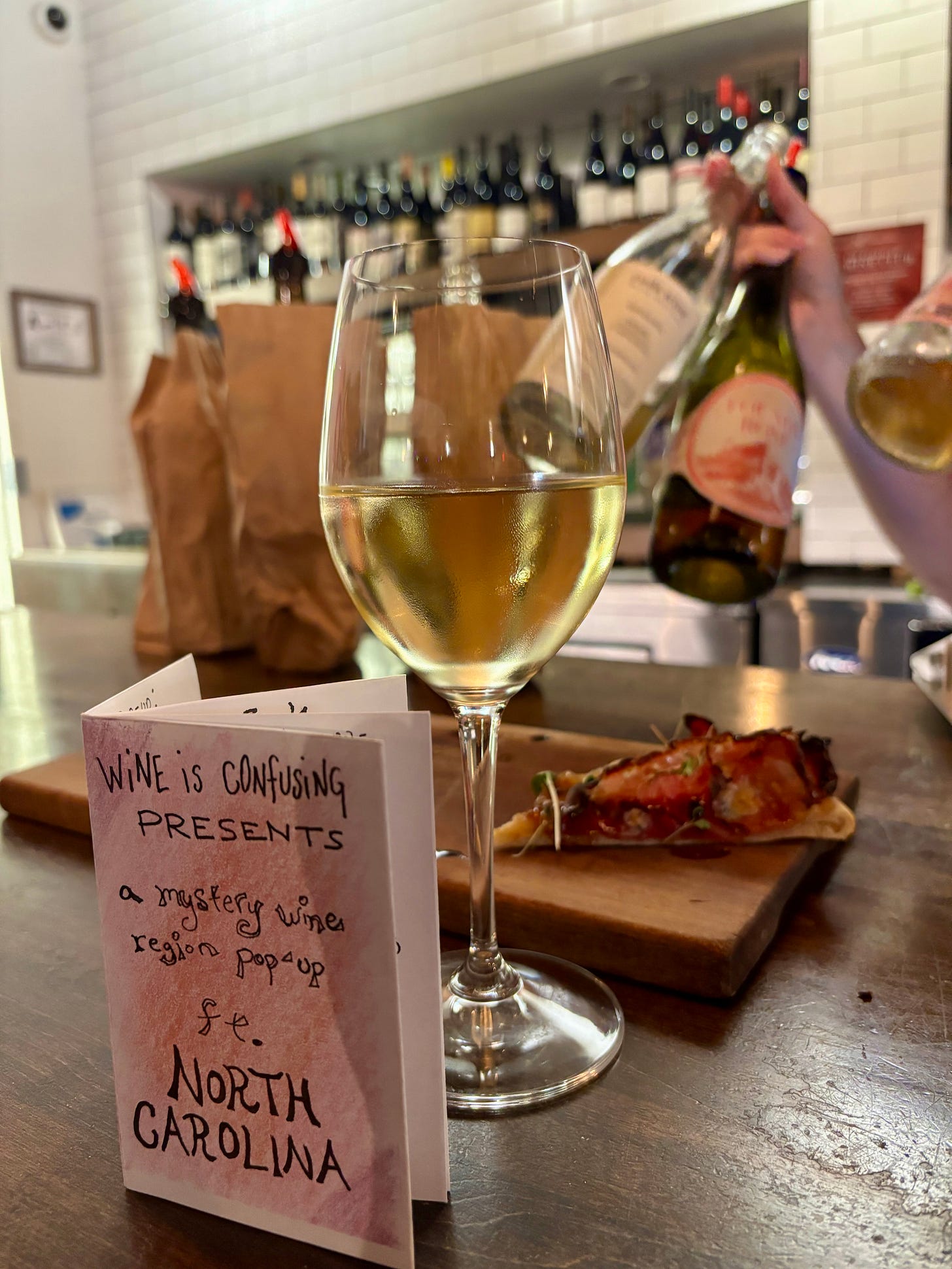

I had been planning this pop-up for months. I called it a Mystery Wine Region Pop-Up, and I’d pour 3 wines in brown bags all coming from the same place. But really it was my way of ambushing people with NC wine—I knew at least half of them would be changed the way I was when I tasted these wines blind.

What I didn’t plan was that the pop-up would land on the weekend after Hurricane Helene swept through Southern Appalachia, bringing the French Broad River to a historic height, and swallowing entire towns in its path.

At the time of pouring these wines, I didn’t understand the extent of the devastation. We still don’t. So much of the region is still without power, water, and cell service. So many people aren’t accounted for but we know that so many didn’t survive the rapidly rising waters between Thursday night and Friday morning. The need is overwhelming: everyone needs everything. From formula to medicine to generators, everyone needs everything.

I had chosen wines that I felt, together, told a different story of North Carolina wine than the one I had been told as an early wine professional. Here we had dry whites made from Vinifera and hybrid grapes, a dry Muscadine and a sparkling Muscadine, pet-nats and rosé from hybrid grapes, a light red blend and an inky red made in the Outer Banks.

Throughout the night, I listened to people guess where in the world these wines could be from. They scribbled on their notecards and ran through their thinking process with me as I stopped by to pour their next wine. Southern France, South Africa, South America. Chardonnay, Malbec, Viognier? Nope. But your logic is right. I would think the same thing.

A few people guessed correctly. Their minds went to Virginia or Crest of the Blue Ridge AVA, and the people who recognized Muscadine echoed the sentiment of other people who know it, telling me, I used to eat them in my backyard growing up. This kind of sense memory is cherished in wine, as is the ability to boast a native grape. But the local wine industry tends to reject Muscadine, leaving it out of the conversation of serious wine, and the more I observe it, the more it feels emblematic of how often we fall short of loving the South. Challenging this has reshaped how I identify as a southern woman.

A few hours before the pop-up, the GM of the wine bar, Jerry Chandler, and I realized that we had a fundraiser built into this thing. Katie, the bartender working that night (and current Resident Sassy Lady) whipped up some flyers, and we told the guests our story: I had driven from the Asheville area the day before, not knowing if I would even be able to get to Charlotte, where I had a pop-up planned. I lived on high ground and was safe, and it wasn’t until I drove 1.5 hours east that my texts came rolling in and I learned of the destruction that had happened minutes from me.

The residents of Jerry’s hometown of Hot Springs, about an hour north, were trapped. Like many other small mountain towns, main access roads had been washed away. Not much help had arrived yet. Jerry’s family has been in Hot Springs forever, and when he tells me stories of his upbringing, the conversation always leads to, “so your memoir is coming out when?”

Just south of Hot Springs, my favorite Appalachian town, Marshall, is also destroyed. Having crossed the bridge between downtown and the island on which a community park sits once a week for months with my dog, I never imaged the river could rise to 24 feet, shoveling mud into historic buildings including the old jail, now the home of Zadie’s Market—best place to get wine and sit on the river. Inside, old documents detailing the history of alcohol, like whiskey prescriptions, along with arrest reports of hard-headed locals like Jerry’s grandmother, lined the wall.

The list of towns surrounding Asheville that have been washed away is overwhelming. Some of these businesses won’t be open for years, and others won’t open again. Without water, the service industry is at a standstill and with it, millions of people who have already had to learn to live without health insurance are now without income as well. Some are also without a place to live and will have to leave.

Me, Jerry, and Katie–the loss of work friends is hard, as everyone working in this industry knows.

At the pop-up, one person told me, “you’re blowing my mind,” surprised that they would be this excited about wineries they can drive to. But I knew that a few of the wineries I was pouring wouldn’t be there. A few days later, I learned that Plēb Urban Winery in the River Arts District was leveled and Euda Wine badly damaged from three feet of flooding.

A week earlier I was getting an eager update by my friend Taylor Greene of Noble Grape, about the Brixx of her vat of grapes beginning to drop. She was making wine for the first time as a guest winemaker at Plēb, and was using it as an opportunity to ask a question along the lines of…what will happen if I do this? Harvest just happened in North Carolina, and a year of work was happily fermenting in tanks across the region.

We raised $1,700 at the pop-up and the following day, and drove two cars of essential supplies to the elementary school in Hot Springs. Mud, rubble, broken windows, and people working together to get donations organized and distributed were the setting of our arrival.

It was never my goal to use these bottles—each of which had been given to me free of charge—to raise funds to recover from a climate disaster. I had printed maximalist, colorful flyers with retro flowers and stripes advertising a playful event, then I poured the wines in shock with tears in my eyes.

But I was reminded of the capacity for a bottle of wine to tell a story far beyond the pruning methods used on its grapevines. And I got the confirmation I was looking for: after dropping paper and pen beside the empty glasses of my guests, I watched as people literally took note of North Carolina wine.

If you’d like to donate elsewhere, please focus on mutual aid and grassroots orgs who will turn your money into help immediately:

Beloved Asheville / Venmo: @BeLoved-Asheville

Pansy Collective / Venmo: @pansycollective

Asheville Survival

WNC Rural Organizing and Resilience (ROAR) / Paypal: ruralorganizingandresilience@gmail.com

Appalachian Medical Solidarity / Asheville Survival Program Cashapp: $streets1de or Venmo: @AppMedSolid

Such a beautiful lament. My heart aches for those who suffer, and the families of those lost.